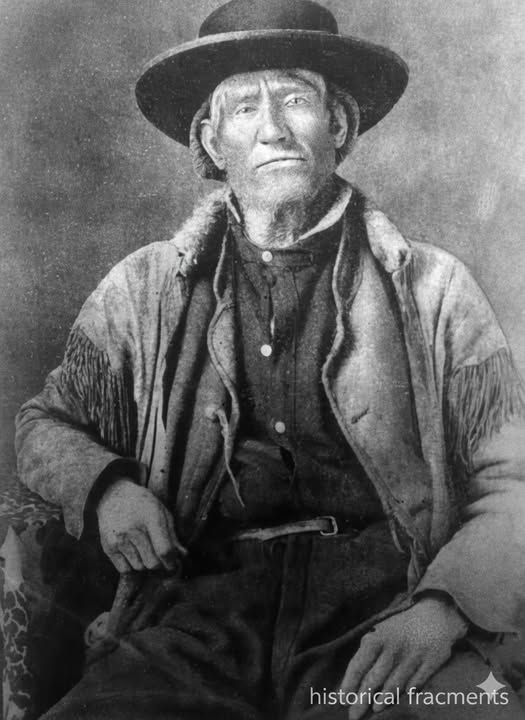

He told them he’d found water that boiled without fire and forests made of stone. They called him a liar. Every word was true.

St. Louis, 1822. An 18-year-old orphan named Jim Bridger worked in a blacksmith shop for pennies. No education. No family. No future anyone could see.

Then he saw a newspaper advertisement that would rewrite his entire existence: “Enterprising Young Men” wanted for a fur trapping expedition into the Rocky Mountains.危険 Pay. Uncertain return. Possible death.

Jim Bridger had nothing to lose and everything to prove. He signed his name and walked away from the only life he’d known.

What followed was nearly six decades of exploration that would make him the most knowledgeable man in America about a landscape most Americans couldn’t even imagine.

Around 1824, young Bridger and fellow trappers followed Utah’s Bear River to discover where it ended. When Bridger reached an enormous body of water stretching beyond sight, he knelt at the shore and tasted it.

Salt. Intense, bitter salt.

He’d reached the Pacific Ocean—or so he believed. He was magnificently wrong. He’d discovered the Great Salt Lake, one of the western hemisphere’s largest saltwater lakes, sitting impossibly in the middle of the desert. He was the first non-Native person to document it.

But that discovery was merely his opening act.

In the late 1820s, Bridger ventured into the Yellowstone region. What he witnessed there defied reality itself.

Water exploding from the earth in columns hundreds of feet high. Pools of boiling liquid in every color imaginable. Mud that bubbled like cooking stew. Entire forests of trees turned completely to stone. Ground that trembled. Air that smelled of sulfur.

When Bridger returned to civilization and described what he’d seen, the response was universal: laughter.

They called him “Old Gabe the Liar.” Journalists mocked his “tall tales.” Even fellow mountain men questioned whether he’d lost his mind.

He hadn’t invented a single detail. He’d simply witnessed Yellowstone four decades before it would become America’s first national park—before the nation was ready to accept that such a place could exist on Earth.

Every impossible thing he described was absolutely real. The world just wasn’t ready to believe him.

For twenty years, Bridger lived as a mountain man, surviving conditions that killed most men within weeks. He learned six Native languages fluently. He married into the Flathead tribe, later marrying twice more after tragedy. He became legendary for reading weather, tracking game, and navigating terrain with supernatural precision.

When the beaver fur market collapsed in the 1840s, Bridger adapted instantly. Thousands of emigrants were beginning the desperate journey west. They needed help.

In 1843, he and partner Louis Vasquez constructed Fort Bridger in southwestern Wyoming. For a decade, that fort served as a critical rest stop where pioneer families could repair wagons, buy supplies, and gather strength before the final brutal push to Oregon or California.

Thousands of lives were saved at Fort Bridger.

As westward expansion accelerated, Bridger became irreplaceable. Military expeditions needed guides who knew every mountain pass. Railroad surveyors needed someone who’d walked every mile of potential routes. Scientific expeditions needed the man who’d accumulated thirty years of geographical knowledge that existed nowhere else.

He guided expeditions well into his sixties, even as his eyesight deteriorated—the price of decades under relentless sun and blinding snow reflecting off endless white peaks.

By the late 1860s, he was nearly blind. His body, destroyed by fifty years of frontier punishment, finally forced him to stop. He retired to a small Missouri farm to live with his daughter, his mountain man era finished.

On July 17, 1881, Jim Bridger died at age 77.

America barely noticed.

The newspapers that had once mocked his “lies” didn’t bother with obituaries. The mountain men who’d first mapped the West had been replaced by railroad tycoons and cattle barons. The wilderness Bridger knew was being conquered, divided, and forgotten.

The man who’d seen the Great Salt Lake when most Americans couldn’t locate Utah on a map died in poverty and obscurity.

But here’s what makes his story extraordinary:

He wasn’t merely an explorer. He was a witness to wonders no one was ready to acknowledge.

His “lies” about Yellowstone became a treasured national park. His fort saved countless pioneer families. His guidance determined railroad routes still carrying freight today. His mental maps, drawn from pure memory, proved astonishingly accurate when modern surveyors checked them decades later.

He transformed from an orphaned, uneducated teenager with zero prospects into one of the most valuable sources of geographical knowledge in 19th-century America.

Today, his name marks the landscape he explored: Fort Bridger State Historic Site, Bridger-Teton National Forest, Bridger Peak, Bridger Pass, Bridger Wilderness Area. His story fills countless Western history books.

But perhaps the most powerful tribute is this:

When modern geologists finally studied Yellowstone’s geothermal features, when surveyors mapped the Great Salt Lake’s chemistry, when historians retraced the Oregon Trail—they discovered that the “absurd fabrications” of an old mountain man were remarkably, almost impossibly precise.

Jim Bridger saw what no one else could see. He spoke truths no one was prepared to hear. And he died before the world caught up to everything he’d known all along.

The newspaper advertisement he answered at 18 promised adventure and danger. It delivered fifty years of discovery that helped build a nation—even if that nation forgot to thank him before he went blind and died.

Not bad for a broke, blind orphan who once mistook a desert lake for the ocean.