The Harlow Children of 1892: A Pennsylvania Case That Still Defies Explanation

In the winter of 1892, Milbrook was an unremarkable farming town in central Pennsylvania. Isolated by forests and poor roads, it rarely appeared in state records beyond crop reports and church registries. That changed after a routine welfare visit led local authorities to a case so unusual that it would linger in county archives—and in local memory—for generations.

According to sheriff’s logs dated February of that year, seven children were found standing inside a barn on the Harlow estate, arranged in a precise formation and refusing to respond to questions. Their adoptive parents, Edgar and Margaret Harlow, were later discovered deceased inside the family home.

What initially appeared to be a tragic case of neglect or illness quickly became something more difficult to categorize. Medical notes, school records, church correspondence, and sworn testimony describe behavior that investigators struggled to explain using the language and knowledge of the time. No criminal charges were filed. No definitive cause of death was established. And the children themselves left behind statements that defied easy interpretation.

Over time, the incident ceased to be treated as a conventional investigation and instead entered local history as “the Harlow children case”—a mixture of documented fact, unresolved questions, and unsettling recollections.

The Discovery at the Harlow Estate

Sheriff Thomas Brennan had served Milbrook for nearly fifteen years when he received the telegraph from Deputy Morris requesting his immediate presence at the Harlow property. The message contained little detail, only noting “concerning conditions involving minors.”

The Harlow farm lay several miles beyond town limits. Winter had rendered the property nearly inaccessible, and the journey took longer than expected. Brennan later noted in his report that the estate appeared “abandoned” despite no formal notice of departure.

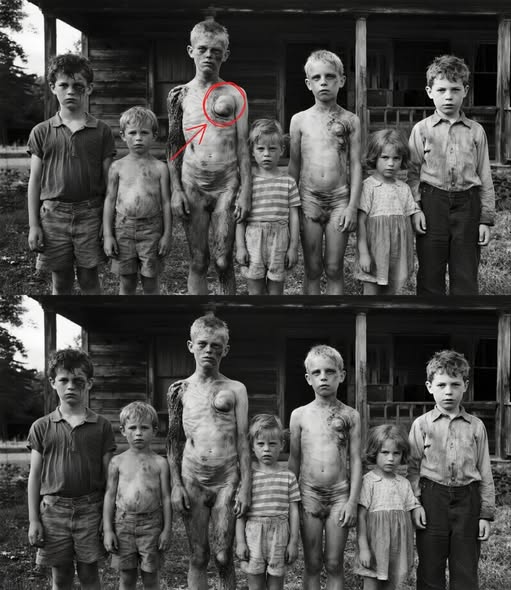

The barn doors stood open. Inside, seven children—estimated to range in age from early childhood to late adolescence—stood shoulder to shoulder. They wore thin, worn clothing inappropriate for the season and showed no visible signs of movement despite the cold.

Deputy Morris testified that the children had remained in that position for an extended period, silent and unresponsive. When Brennan attempted to address them, they did not reply immediately. Only after repeated questioning did the eldest child speak, offering statements that officials later described as “unusual in tone and phrasing.”

The children followed the sheriff without protest when he entered the main house. There, in the parlor, Edgar and Margaret Harlow were found seated upright in their chairs, hands folded neatly in their laps. While death appeared to have occurred some time earlier, the bodies had been carefully arranged. Fresh flowers rested in Margaret Harlow’s hands.

Someone had been tending to them.

The Harlows’ Arrival in Milbrook

Edgar and Margaret Harlow arrived in Milbrook in the autumn of 1889, purchasing the long-vacant Witmore estate at a price many considered suspiciously low. The property had remained unclaimed since the Witmore family departed suddenly decades earlier, leaving behind furniture and livestock.

The Harlows, however, appeared unconcerned by local superstition. Edgar introduced himself as a former educator from Philadelphia seeking a quieter life. Margaret joined the town’s women’s auxiliary and participated in church activities, though several members later recalled her demeanor as distant.

For nearly six months, the couple lived alone. Then, in the spring of 1890, the children appeared.

No arrival was witnessed. No explanation was offered. One Sunday morning, Margaret Harlow attended church with seven children dressed identically in muted gray clothing. When questioned, she introduced them simply as her own.

Their names—Ruth, Rebecca, Rachel, Robert, Richard, Roland, and Raphael—followed an alphabetical pattern that some townspeople found curious. Their ages were unclear, though they appeared to span a wide range.

The children spoke rarely. When they did, multiple witnesses noted an unusual cadence to their speech, described in later testimony as “formal,” “measured,” and “lacking spontaneity.”

School Records and Medical Concerns

The children enrolled in the local school within a month. Miss Sarah Hendrix, their teacher, later provided a sworn statement describing their academic performance as flawless. They made no errors in arithmetic, wrote with perfect penmanship from the first day, and recited facts with mechanical precision.

Yet they struggled with tasks requiring imagination. When asked to draw or write creatively, they remained motionless, staring at blank pages until the exercise ended.

“It was as if they knew answers,” Hendrix testified, “but did not understand expression.”

Dr. Herman Walsh, the town physician, attempted to conduct routine examinations. The Harlows refused on religious grounds, citing beliefs “older than the country itself.” Walsh later wrote privately of concerns regarding the children’s skin tone and eye reflections, though he admitted he lacked evidence to pursue the matter further.

The Parents’ Deaths

By January 1892, the Harlows stopped appearing in town. At first, this absence raised little alarm. Harsh winters often isolated rural families.

When Deputy Morris visited the estate weeks later, he found the barn doors open—and the children waiting.

Inside the home, Edgar and Margaret Harlow were deceased. No signs of violence were immediately apparent. The cause of death was never conclusively determined. The cold had preserved the bodies, complicating medical examination.

What disturbed investigators was not only the deaths, but the careful maintenance of the household afterward. The floors were clean. The furniture was arranged. Flowers had been replaced regularly.

According to later testimony, the children acknowledged caring for the bodies. They described this as “appropriate behavior.”

The Interrogation at Town Hall

The children were questioned in the Milbrook Town Hall rather than the jail. Present were Sheriff Brennan, Dr. Walsh, Reverend Mitchell, the mayor, and a county stenographer.

Transcripts from the session reveal responses that officials found deeply unsettling—not for explicit threats, but for their detachment.

When asked how long they had lived with the Harlows, the eldest child stated they had come “to learn” and referred to the parents as “teachers.” The nature of this learning was never clearly defined.

Pressed further, the children described observation, imitation, and correction. Reverend Mitchell later wrote that their language “resembled metaphor rather than confession.”

At one point, the children referenced grief, loss, and replacement. The Harlows, they said, had lost children years earlier and were “willing to overlook inconsistencies.”

Investigators debated whether these statements reflected trauma, shared delusion, or deliberate manipulation. No consensus was reached.

Aftermath and Disappearance from Records

Following the interrogation, the children were transferred to state care. Official documentation ends abruptly. No burial records, institutional files, or adoption papers have been conclusively linked to them.

The case was quietly closed.

Over time, historians proposed explanations ranging from psychological contagion to misinterpretation amplified by grief and isolation. Others pointed to poor record-keeping and the tendency of memory to distort.

In Milbrook, however, the story endured in another form. Families spoke of it in lowered voices. Children were warned not to wander near abandoned properties. The Harlow estate remained unoccupied.

An Unanswered Case

More than a century later, the Harlow children case remains unresolved. No single explanation accounts for every detail preserved in the records.

Perhaps it was a convergence of grief, trauma, and human projection. Perhaps it was a cautionary tale shaped by fear and time. Or perhaps it was simply a reminder of how easily certainty collapses when tragedy meets isolation.

What remains undeniable is that in February 1892, seven children were found standing silently in a Pennsylvania barn—and nothing about what followed fit neatly into the categories investigators expected.

Some cases end with answers. Others become stories people tell when facts alone feel insufficient.

The Harlow children belong to the latter.