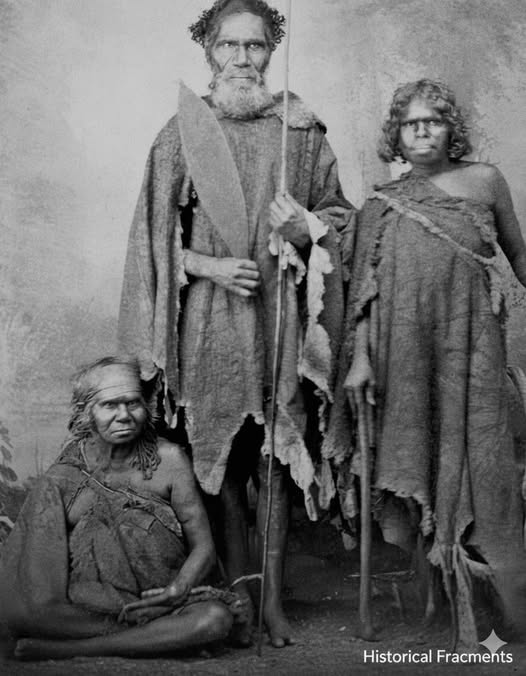

This photograph from the 1860s captures something most history books erased—and what it reveals will change how you see Australia’s past.

Somewhere between 1860 and 1890, in the south-west region of Western Australia, a group of Noongar elders gathered before a camera. It was a time when their world was being violently transformed, when disease, displacement, and dispossession threatened everything their ancestors had built over tens of thousands of years.

Yet in this single photograph, you see something powerful: dignity, strength, and the visible thread of culture that colonization tried but failed to break.

The elders are wrapped in kangaroo-skin cloaks, garments that represented far more than warmth or protection from the elements. Each cloak was a masterpiece of knowledge and artistry, created through careful hunting, precise preparation, and skilled craftsmanship passed down through countless generations.

Look closer at the patterns etched into those cloaks. Those aren’t just decorations. Each design told a story. They recorded identity—who you were, which family you belonged to, which ancestor’s spirit guided you. They mapped Country—the sacred land you were responsible for, the places your people had cared for since time immemorial. They held memory—significant events, spiritual connections, knowledge that words alone couldn’t capture.

In a culture that thrived without written language, these cloaks were living documents, carrying information as precious as any library.

One elder holds a spear thrower—a woomera—in his hands. To unfamiliar eyes, it might seem simple. But that tool represents thousands of years of engineering genius, a technology so effective that it increased throwing distance and accuracy in ways that gave Aboriginal people mastery over this vast, challenging continent.

Every detail in this photograph reflects something profound: the skill it took to survive and thrive in environments others found impossible, the knowledge systems complex enough to manage an entire continent sustainably for over 65,000 years, the resilience to maintain culture even as the world around them was being dismantled.

The photograph was taken by James Manning Jr., a Perth-based photographer who traveled extensively through Western Australia during the late 19th century. While many photographers of that era captured Aboriginal people through a lens of colonial curiosity or condescension, this image—whether intentionally or not—preserved something invaluable: evidence of sophisticated culture, not the “primitive” stereotype colonizers wanted to believe in.

By the time this photograph was taken, the Noongar people had already endured decades of devastating change. Diseases introduced by Europeans had swept through communities. Traditional lands had been seized and fenced. Languages were being forbidden. Children were being taken from families.

Yet here they stand—wrapped in their cloaks, holding their tools, their eyes meeting the camera with the quiet authority of people who knew exactly who they were.

This isn’t a photograph of a “dying race,” as colonial Australia liked to claim. This is evidence of survival. Of cultural continuity. Of knowledge systems too strong to be erased, even by the deliberate efforts of those who tried.

Today, Noongar people continue to live on and care for their Country in south-west Western Australia. Their languages are being revitalized. Their stories are being reclaimed. Their connection to land that stretches back tens of thousands of years remains unbroken.

The kangaroo-skin cloaks may be rare now—many were lost, destroyed, or locked away in museums far from home—but the knowledge they represented never disappeared. It lived on in families, in memories, in the continued connection to Country that no government policy could sever.

This photograph is more than a historical curiosity. It’s a testament to something most people never learned in school: Aboriginal cultures weren’t primitive societies waiting to be “civilized.” They were—and are—complex, sophisticated civilizations with knowledge systems, technologies, and philosophies that sustained people and land in harmony for longer than almost any other human culture on Earth.

Every time you see images like this, remember: these weren’t people lost to history. They’re somebody’s great-great-grandparents. Their descendants walk among us today, carrying forward the same connection to Country, the same cultural knowledge, the same unbroken thread that stretches back further than the pyramids, further than written language, further than almost anything else humans have created.

The strength in this photograph isn’t just historical. It’s present. It’s ongoing. It’s the story of survival that continues every single day.

Culture, survival, and connection to Country—not as museum pieces or romantic notions, but as living realities that colonization tried to destroy and failed.

That’s the real power in this image. Not what was lost, but what could never be taken away.