A team of gas utility workers laying pipes in northern Lima, Peru, stumbled upon an ancient discovery during their work, uncovering a 1,000-year-old pre-Inca mummy—one of a string of archaeological finds in a city rich with a historical past. The find was made in the Puente Piedra district, where workers were digging trenches to expand the natural gas network.

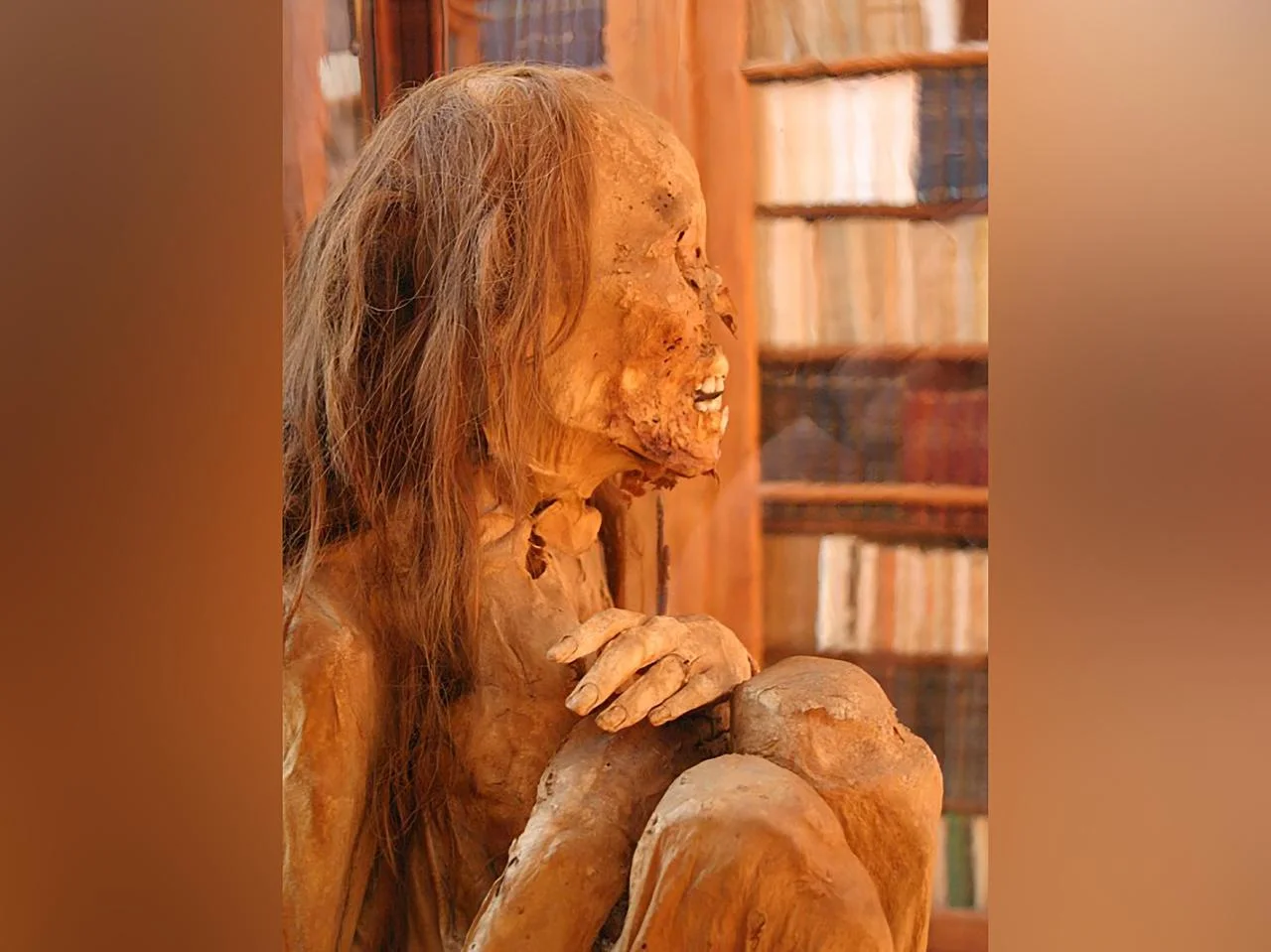

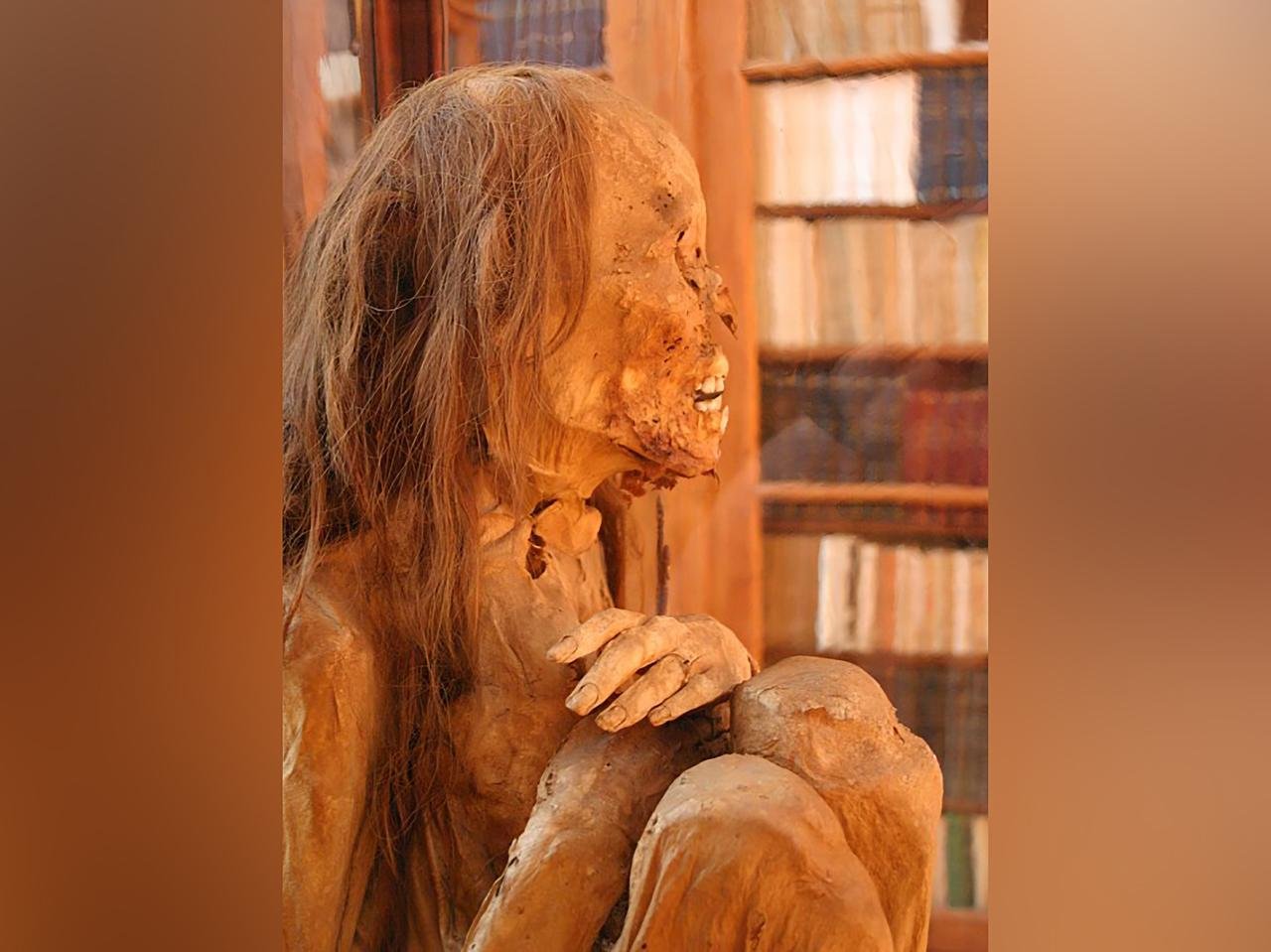

The find was just 20 inches (50 centimeters) beneath the ground when workers came upon the trunk of a huarango tree—historically used as a tomb marker in Peru’s coastal area. The presence of the tree indicated the probable presence of a grave. While excavating further, archaeologists discovered the remains of a teenager between the ages of 10 and 15 who was buried in a seated position with arms and legs bent, wrapped in a shroud with ritual objects.

“The burial and the objects correspond to a style that developed between 1000 and 1200 CE,” said archaeologist Jesus Bahamonde, scientific coordinator of the Calidda gas company. He further noted that the burial contained calabash gourds and a set of ceramic items—plates, jugs, and bottles—adorned with geometric motifs and figures of fishermen. Such artistic features and burial style point to the Chancay culture, a coastal culture that existed from the 11th to the 15th century in central Peru.

Jose Aliaga, an archaeologist with utility Cálidda, said the mummy retains visible characteristics such as dark brown hair and was discovered in a seated position and wrapped up, characteristic of funerary attitudes among ancient Peruvian cultures. Such a burial suggests regional cultural mummification practices in which arid coastal conditions naturally preserved bodies.

Although the find is stunning, it is not particularly surprising. Lima, a sprawling city of 10 million people, overlays an ancient landscape with more than 500 archaeological sites.

Peru requires all utility companies to employ archaeologists whenever subsurface construction is undertaken because there is a strong possibility of encountering heritage artifacts. Cálidda has uncovered more than 2,200 archaeological items during routine infrastructure work.

This recent discovery adds another valuable fragment to Peru’s historical jigsaw puzzle and underlines the richness of culture that lies beneath the surface of Lima’s modern streets.

Hidden under the urban hubbub of Lima’s Puente Piedra area, workers laying out Peru’s network of natural gas pipelines have inadvertently made an astonishing archaeological discovery: the mummified body of a young woman buried more than 1,000 years ago. Only 0.5 meters (1.64 feet) under Santa Patricia Avenue, enveloped in a funerary package and fenced in by ceramics and organic offerings, this pre-Inca grave is linked to one of coastal Peru’s lesser-known ancient cultures: the Chancay civilization.

A Burial in the Shadow of the City

The mummy, unearthed by Cálidda utility workers, sat upright, her dark brown hair still intact after a thousand years underground, reports The Associated Press. Even buried under decades of urban expansion, the tomb was surprisingly well preserved.

Archaeologist José Aliaga testified that the workers immediately stopped construction and alerted the authorities when they discovered evidence of a grave — a measure necessitated by the fact that Lima’s ancient remains lie under much of its contemporary infrastructure.

Lima, which was previously a sequence of productive river valleys occupied for thousands of years prior to the Spanish conquest, today is a city of 10 million superimposed on over 400 archaeological sites.

As Pieter Van Dalen, dean of Peru’s College of Archaeologists, explains, “It is quite normal to encounter archaeological remains along the Peruvian coast, including Lima… above all funerary components: tombs, burials, and mummified bodies.”

Pre-Incan child mummy, a predominant part of the cultural history of Peru. (HimmelrichPR/CC BY-SA 2.0)

The woman had been mummified in keeping with pre-Hispanic coastal custom, her body probably naturally dehydrated by the dry climate of the area. Buried with her hands over her face in the classic position, the young woman lay with nine vessels of ceramics, four shellfish-filled calabash gourds, and other ceremonial offerings — all indications of a ritual send-off performed with respect and care.

Chancay Legacy: Through Clay and Cloth

The burial has been attributed to the Chancay culture by archaeologists, a seacoast civilization that existed between 1000 and 1470 AD in the valleys between the Chillón and Chancay river, just prior to the Incas’ conquest of the region. Developing following the fall of the Wari state, they became a prominent, but decentralized, regional polity.

Differing from their Chimú neighbors, however, the Chancay functioned through a loose network of interlinked communities. They learned irrigated desert agriculture, fished on reed craft known as caballitos de totora, and did a great deal of trade inland and along the coast.

The grave offerings that were unearthed from the tomb — black-on-white pottery, tricolor pots, and ritual gourds — are signatures of Chancay workmanship. Not only do they demonstrate taste in aesthetics, but also offer vital information regarding the social status of the person, reports The Greek Reporter.

“The fact that there are well-crafted ceramics and organic offerings indicates she was possibly an important member of her society,” stated archaeologist Jesús Bahamonde, who oversees Lima’s archaeological surveillance at Cálidda.

Chancay folk were particularly famous for their cloth and for their signature cuchimilco statues — ceramic guardians with arms open and eyes glaring, sometimes buried with the dead to guard them. While none were present in this grave, the burial bundle and dedications fit into the same ritual model that underlay Chancay funeral rites.

Although ultimately absorbed by the Chimú and eventually the Inca, the Chancay left a full material legacy. Their craft remains in museums—such as Larco in Lima, where a painted ceramic cuchimilco remains, painted directly onto slip and displaying unburnished clay texture.

Modern scholars see the Chancay not as a centralised empire but as a confederated cultural powerhouse—strong, aesthetic, and religiously complex. Their fascinating mix of mundane practicality, ritual purpose, and aesthetic embellishment provide access to the interlocked spheres of functionality and belief in pre‑Inca coastal culture.